We have published a new paper “The Policy Potential of Measuring Internet Outages” in TPRC46, the Research Conference on Communications, Information and Internet Policy, to be presented on September 21, 2018 at the American University, Washington College of Law.

From the abstract of our paper:

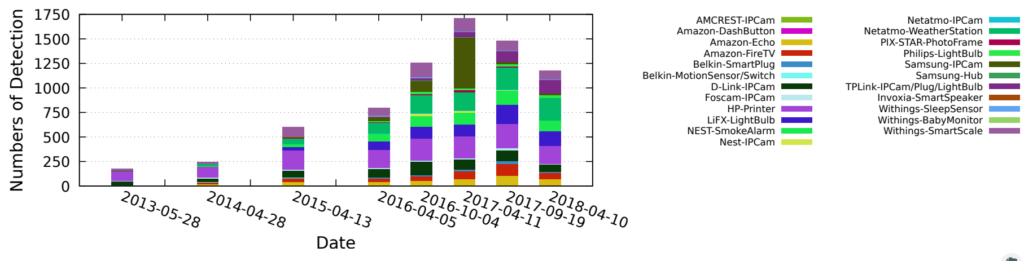

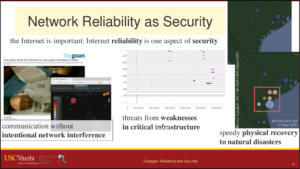

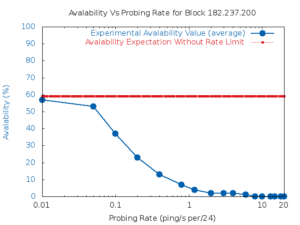

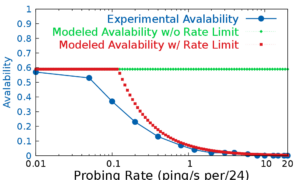

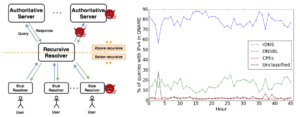

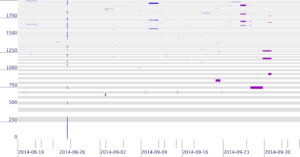

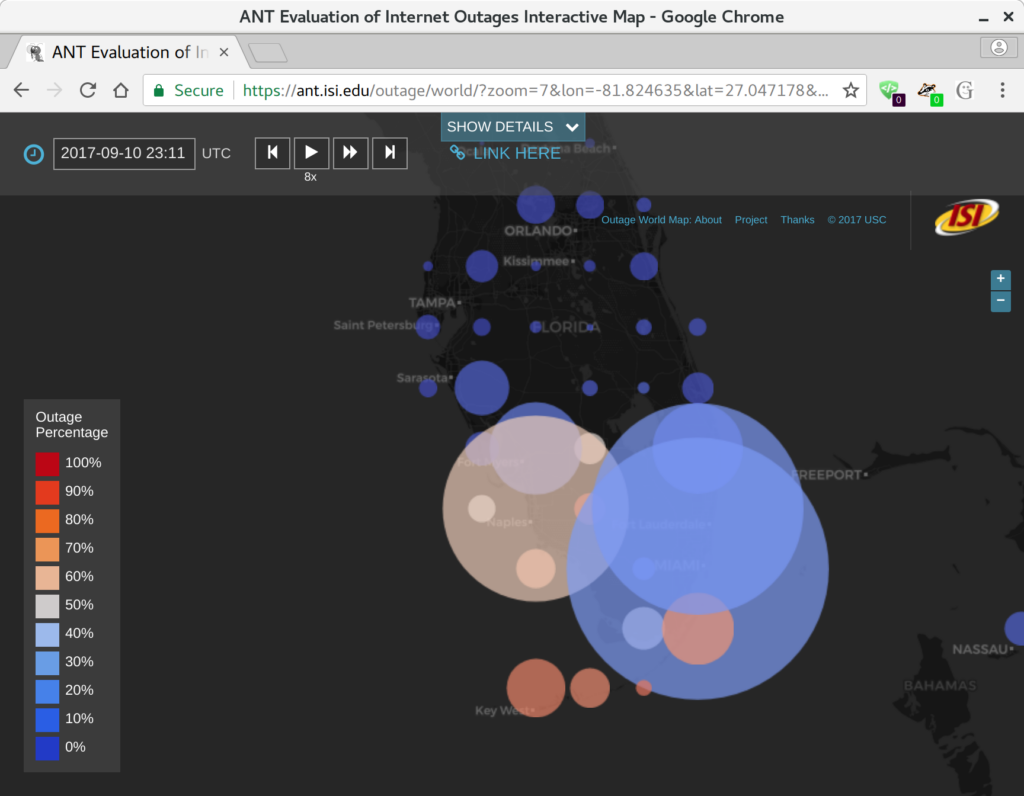

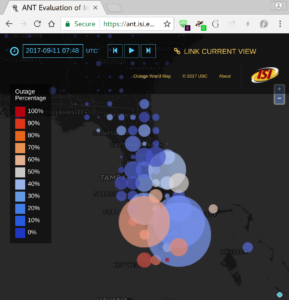

Today it is possible to evaluate the reliability of the Internet. Prior approaches to measure network reliability required telecommunications providers reporting the status of their own networks, resulting in limits on the precision, timeliness, and availability of the results. Recent work in Internet measurement has shown that network outages can be observed with active measurements from a few sites, and from passive measurements of network telescopes (large, unused address space) or large network services such as content-delivery networks. We suggest that these kinds of *third-party* observations of network outages can provide data that is precise and timely. We discuss early results of Trinocular, an outage detection system using active probing developed at the University of Southern California. Trinocular has been operating continuously since November 2013, and we provide (at no charge) data covering about 4 million network blocks from around the world. This paper describes some results of Trinocular showing outages in a large U.S. Internet Service Provider, and those resulting from the 2017 Hurricane Irma in Florida. Our data shows the impact of the Broadband America policy for always-on networks, and we discuss how it might be used to address future policy questions and assist in disaster planning and recovery.

Data we describe in this paper is at https://ant.isi.edu/datasets/outage/, with visualizations at https://ant.isi.edu/outage/world/.

This paper is joint work of John Heideman, Yuri Pradkin, and Guillermo Baltra from USC/ISI, with work carried out as part of LACANIC and DIVOICE projects with DHS S&T/CSD support.